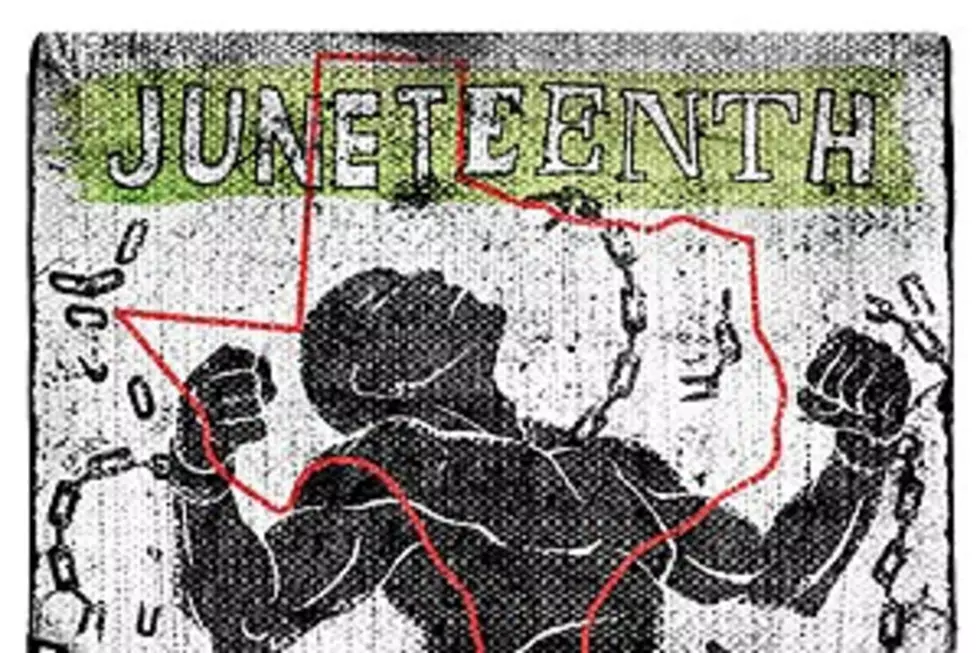

How Texas Turned A Slave Legacy Into an International Celebration of Freedom

Back when Galveston was a busy port with a booming commercial district, a hardware store owner named James Moreau Brown sold his business and bought a slave named Alek, who was a stone mason. In 1859, Brown, who soon became the fifth-richest man in Texas, and Alek began building a Victorian mansion.

Brown called his grand residence Ashton Villa and threw lavish parties, including one of the best annual New Year's balls Galveston had ever seen. And when Ulysses S. Grant was elected president, Ashton Villa was the only private dwelling he entered while in Galveston.

That is fitting, because it is also the place where, on June 19, 1865, one of Grant's generals stood on the balcony to read a proclamation that would change everything for Texas. General Order No. 3: All slaves are free. The date is crucial; slaves in Texas were finally given this news two years after the Emancipation Proclamation had already freed them.

Powerful white men who owned human beings (of higher or equal value to prized livestock) had successfully derailed any verbal confirmation of Abraham Lincoln's 1863 proclamation to end slavery. Slaves were forbidden to read. Rumors of freedom had been killed. Desperate masters from other states were even able to hide their human property in Texas, relishing the thought of staying a few miles ahead of the conquering Union Army.

But once New Orleans fell, it was just a matter of time before owners could no longer conceal black bodies. Union General Gordon Granger was dispatched to restore calm in lawless pockets of Texas.

Upon arriving in Galveston, Granger climbed up to the balcony of the Ashton Villa and read General Order No. 3: "The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and free laborer."

Slaves cried and danced for hours.! Shouts of, "We's free! We's free!" were heard for miles, although thousands had no idea what freedom meant or how to experience it. However, they knew it had to be better than eating hog scraps, wearing tattered clothes, living in slave quarters, and working for zero dollars.

Slaves were known for shortening words, and it wouldn't be long before the words, June and nineteenth were wed to become what we know today as, "Juneteenth".

Unfortunately, although the proclamation gave them everything, it provided them nothing. Thousands of black people left slavery without a strategy for survival. Some adhered to Granger's advice to remain in Texas to "work for wages" as sharecroppers, ranch hands and domestics.

Although a true Texas holiday, some of the largest Juneteenth celebrations in America have been in San Francisco, Denver, Milwaukee and Philadelphia. Organizers offer parades, lectures, job fairs, jumping-the-broom love stories, health exhibits, food and poetry.

More From Majic 93.3